1147

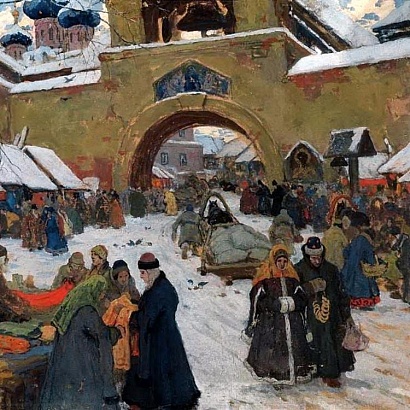

«Come to me, brother, to Moscow»

The first reference to Moscow, preserved in the Ipatiev Monastery Chronicles, were the words written in 1147 by Prince Yury Dolgoruky of Vladimir to his ally Prince Svyatoslav Olgovich of Novgorod, inviting him to come feast in the village of Moscow. Archaeological evidence shows that a settlement on the banks of the Moscow River already existed in the 8th and 9th centuries. People lived on Borovitsky Hill, and the Zaryadye grasslands were used for haymaking, grazing, and fishing. This area was home to one of the prince’s residences in the middle of the 12th century. At the time, Moscow was starting to grow and expand at a fast pace. When an invitation was sent to the prince, as described in the Chronicles, it was a rich village with a princely estate on the embankment of an important transport artery – the Moscow River. Goods for the prince’s court began to arrive on the docks in Zaryadye via river boats, which brought in messengers, merchants, and tributaries from other territories under the prince’s rule.

1156

First Kremlin and Velikaya Ulitsa

In 1156 the village flourished into a city under the watchful eye of Yury Dolgoruky. To protect himself from raids, he ordered the construction of a wooden wall and towers to enclose the central part of the Borovitsky hill settlement, which included a church, the prince’s palace, barracks, and storage. This was the first manifestation of the Moscow Kremlin. At the same time, a road from the Zaryadye docks to the fortified Borovitsky hill was formed for transporting goods from river vessels to Moscow. Houses were built along the road, each with their own gardens and housekeeping. And this was how Zaryadye became home to the town’s first street Velikaya Ulitsa, one of the busiest transport arteries in medieval Moscow. The street was paved with wooden blocks and arrived at the Kremlin where the present day Konstantino-Eleninsky Tower stands. The lower river bank parts near the Kremlin (called Podol and Poreche), including Zaryadye, became a bustling village about a kilometre from Moscow.

1238

Mongolian invasion: destruction and restoration of Zaryadye

The Zaryadye village was destroyed during the Mongol invasion of Moscow in 1238. When the Rossiya Hotel was being excavated, traces of the pre-Mongolian horde were found: bracelets, blue glass beads, a spindle, a cross, locks, and ceramic fragments. The campaigns of Batu Khan led to significant geopolitical changes in Ancient Rus, including moving the ancient capital from Kievan Rus to Suzdal, the territory on which Moscow was located. The city prospered and grew rich. In 1365, construction of the white stone walls of the Moscow Kremlin began. At the same time, according to some sources, the name Zaryadye first appeared in records. Another version states that the Zaryadye area was formally named only some 150 years later, in the 16th century. Researchers associate the etymology with its location relative to the Kremlin and Red Square, which at the time was a large bazaar filled with stalls. Thus, zaryadye, or ‘behind the stalls’ (in Russian, ‘za’ is behind, and ‘ryad’ is stall). In the 14th century, at the very beginning of Velikaya Ulitsa, the Church of Saint Nikolay, the patron of merchant travellers and navigators, was built.

1485

The rise of Moscow and the fall of Velikaya Ulitsa

During the reign of Ivan Vasilyevich, the Grand Principality of Moscow was freed from Mongol control and began annexing neighbouring lands for itself. In 1485, Italian architects were invited to Moscow and began building the new walls of the Kremlin. The city became the capital of a vast country. Land routes to all corners of Russia were built, and delivery of goods along the river gradually subsided. Zaryadye and Velikaya Ulitsa, situated on the plain of the hill, lost their importance as transport hubs but still maintained their status as a commercial center. Gostiny Dvor, an important transport junction for wealthy merchants, and Mytny Dvor, a medieval customs point where imported goods were evaluated and tariffs collected, were both located in Zaryadye. At the time, Zaryadye was a densely populated suburban home to parish churches.

1521

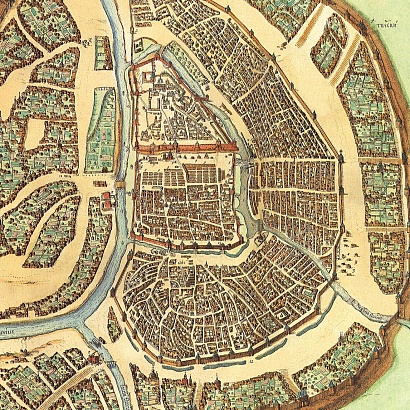

Behind the Kitay Gorod wall

In 1521, Moscow was attacked by Mehmed Giray, the Crimean khan. Not daring to storm the new Kremlin, he burned down surrounding settlements. Residents took shelter inside the Kremlin, which led to massive overcrowding. After the retreat of the Crimean khan, Grade Duke Vasily decided to protect the settlements with a fortified wall. Again, an Italian architect was invited to construct the wall, and he was given the Russian name Petrok Maly. Modest in height but vast and widespread, the Kitay Gorod wall was designed to repel artillery fire, was protected by eight towers, and had six gates on different sides leading in and out. According to one account, the name Kitay Gorod (in Russian, ‘China Town’) originated from the Italian word ‘chita’ (city), which is how the Italian architect called the ‘lower town’ he was building a wall around. The new barrier blocked Zaryadye’s direct access to the river from the east and south. By the beginning of the 16th century, Velikaya Ulitsa, having lost its significance, began to disintegrate.

1557

The English ‘embassy’ and Tsar’s palace

In 1557 English merchants – with the blessing of the young tsar Ivan Vasilyevich – settled in Zaryadye at the former court of Ivan Bobrishchev, the Tsar’s attendant. The English sent gun powder, tin metal, leather, and furs to Moscow. The death of Fyodor Ioannovich in 1598 brought the Rurik dynasty to an end. After the reign of Boris Godunov and the Time of Troubles, Kitay Gorod was attacked by Prince Pozharsky and the Cossacks in 1612. The Zemsky Sobor (Assembly of Land) elected a representative of the Romanov-Zakharin-Yuyev family to rule. The Zaryadye settlement was given a special status and was restored with the ascension of the first Romanov. According to some sources, it was restored because Mikhail Fyodorovich lived in his grandfather’s old estate in Zaryadye and not in the Kremlin’s Golden Chamber during the first years of his rule.

1626

Old English Court

After another fire ravaged Zaryadye and its wooden buildings in 1626, the royal family moved to the Kremlin, and the Zaryadye palace was given the name ‘Old English Court’. Around 1630, the palace was handed over to the Znamensky Monastery. In 1649, the old English farmhouse on Varvarka, which had stood for almost one hundred years, was seized and English merchants were driven out due to the Tsar’s disgust over the execution of King Charles I during the English Revolution. After the fire in 1626, Zaryadye’s core structural design was restored, which remained until the demolition of the area in the mid 20th century, which reconfigured the entire area. The side streets Zaryadyevsky, Maly Znamensky (later Maksimovsky), Pskovsky, and Bolshoy Znamensky (later Yeletsky), and Ershovskiy alleys were positioned to descend from Varvarka street down to the Kitay Gorod wall.

1668

Stone foundation gates and military post

In 1668, another fire destroyed most of the wooden buildings in Kitay Gorod and Zaryadye. By the end of the 17th century, the Kosmodemyanskaya gate (where Velikaya Ulitsa once led) of the Kitay Gorod wall was covered with bricks, and later stones, in an attempt to fireproof the towers. In anticipation of the Swedish campaign advancing towards Moscow in 1707, Peter I had all the gates fortified with stone foundations, and protective walls were built around the towers. During this time, Zaryadye turned into a military camp, and residents were forced to put up soldiers in their homes. But Swedish King Carl XII settled against invading Moscow and decided first to go to the country's southern lands, where by June 27, 1709 he was defeated by Russian troops in the Battle of Poltava. Meanwhile in Zaryadye the summer of 1709 saw pedestrian passages through the Nikolsky, Ilyinsky, and Varvarka gates appear.

1812

Zaryadye after the Patriotic War of 1812

Napoleon advanced and reached the Kremlin on September 15, 1812, but fires had suddenly broken out across Moscow, engulfing the entire city centre. After Napoleon and the French were expelled, simple landowners didn’t have the means to rebuild. Land and property redistribution took place, and most of the land in Zaryadye was transferred to wealthy nobles and merchants. New construction fully developed the district, which kept the same layout until its demolition in the 20th century. A staircase winded down from the respectable Varvarka to the Zaryadye alleys, nicknamed “small and spiff” by Moscow poet Ivan Belousov. All of the alleys, with the exception of Pskovsky, came to a dead end at the Kitay Gorod wall. Two and three-story homes were built on these streets and rented by petty bourgeois craftsmen: the first floor was the shop and storefront, and the second and third floors were living spaces. The basements, the cheapest housing option in Moscow, were also inhabited.

1826

Jewish quarter

In 1826, Prince Alexander Golitsyn, Moscow’s Governor General, allowed Jewish merchants and artisans to come work in Moscow. The Glebovsky residence on Bolshoy Znamensky alley in Zaryadye was designated for new arrivals. A synagogue was built in the courtyard of the Glebovsky residence, and Jewish craftsmen settled nearby. Kosher bakeries, such as ‘Drozdons Bakery’ lined the alley of craft workshops with names like ‘Benjaminson’s Felt Fabrics’ and ‘Ancelovici’s Watches’. Peter Sytin, author of The History of Planning and Building Moscow noted that by the middle of the 19th century, there was no space left to construct wooden buildings in Kitay Gorod “except for a few sheds in Zaryadye.” These sheds continued to exist until the 20th century and can be found in old photographs.

1859

Palace of the Romanov Boyars

Emperor Alexander II visited the remains of the Romanov-Zakharyiny-Yuryev residence in 1856. After 200 years in the possession of the Znamensky Monastery, the chambers were in a state of disrepair and heavily redesigned. The young emperor bought the palace from the monastery and instructed Fyodor Richter to restore the family monument. Using archival materials and preserved examples of Russian architecture from the 16th-18th centuries, the architect was able to nearly duplicate the original. In August 1859, the Palace of the Romanov Boyars museum was opened, and the family gave the cradle of the first Romanov on the throne – Mikhail Fyodorovich – to put on display. The last Russian tsar, Nicolas II, visited the museum in May 1913 to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the family’s dynasty. Just years later, the monarchy and dynasty collapsed.

1906

Slum (Run-down neighborhood)

In the 19th century, the entire Vasilievsky quarter was densely occupied and built up, with vegetable gardens and clotheslines in the streets. Wooden and brick sheds were attached along the inside of the Kitay Gorod wall. Due to the many different layers and materials used over the years, in some places, the wall had completely disappeared. Over time, the Zaryadye neighbourhood had become run down. Tailors, shoemakers, button makers, glove makers, fur weavers, locksmiths, metal workers, and typists of Russian, Jewish, and other descent, lived in poverty and in close quarters. In 1906, at the corner of the Pskovsky and Morinsky alleyways, architect Lev Kravetsky designed a four-story U-shaped apartment building with no outside entrances but a covered courtyard that led up to modest apartments.

1935

People's Commissariat of Heavy Industry

In March 1918, the Soviet government moved the capital from Saint Petersburg to Moscow. Official party offices occupied several blocks between Ilyinka and Varvarka: Zaryadye had again become the centre of power. Immediately following the Civil War (1917-1922), the Kitay Gorod wall was reconstructed, resulting in the removal of stalls from the outside wall along the Moscow River embankment. On the inner wall, unregistered construction was also torn down, and a pedestrian passage appeared for the first time in a long time. But these measures only slightly alleviated the problem of having a run-down neighbourhood in the very centre of the new proletarian capital. In the 1935 new city plan, the Zaryadye district was cleared out for the construction of the grand building of the Peoples Commissariat (Narkomat) of Heavy Industry. The best Soviet architects took part in the contest to design the building. However, in 1937, after the death of the institute’s head, Sergo Ordzhonikidze, the decision to construct it in Zaryadye was cancelled.

1967

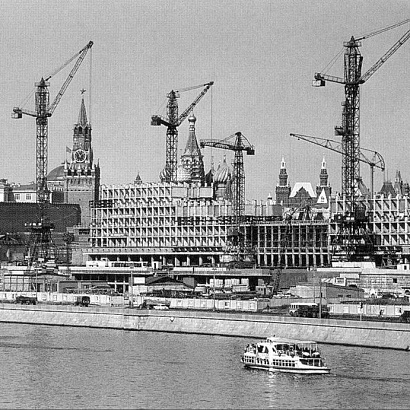

The ‘eighth sister’ and Rossiya Hotel

The old buildings in Zaryadye were demolished up through the end of the 1940s when the space was cleared and the foundation was laid for a 32-story post-war Stalinist skyscraper, the ‘eighth sister’ designed by architect Dmitry Chechulin to join the other seven white, layer-cake style buildings in Moscow. However, after the death of Stalin, construction of the tower was halted, and for many years remained an abandoned construction site, a microcosm for many other grand Soviet projects. The arrival of the Khrushchev Thaw decided the fate of Zaryadye: in the spirit of a new chapter of Soviet openness to the rest of the world, the Rossiya Hotel, designed by the same architect, was built in 1967. At the time, it was the largest hotel in the world. Very few historical monuments in Zaryadye were preserved, but the architect and restorer Pyotr Baranovsky went to great efforts to salvage part of the Kitay Gorod wall and to reconstruct the Old English Court.

1978

Full-fledged socialism on display

With restaurants, cafes, a hair salon, and a cinema, Rossiya Hotel was the first of a new breed of Soviet entertainment complexes. The Zaryadye movie theatre featured two halls with a 775-seat capacity that premiered Soviet films and sometimes allowed foreign films. Atop the cinema was the State Central Concert Hall Rossiya, which seated 2500 people. The hotel had 3,182 rooms equipped with imported appliances – the hotel was supposed to show foreign guests from capitalist countries the high level of comfort and service in a fully-developed socialist country. In December 1978, the hotel hosted the German disco group Boney M, who performed 10 concerts in the State Central Concert Hall Rossiya.

2006

Demolition of Rossiya Hotel

Since the advent of Rossiya Hotel in Zaryadye, its aesthetic qualities caused much controversy and reprimanding among Muscovites. In the architectural world, the creation was called “Chechulin’s storage chest” behind the architect’s back. At the beginning of the 21st century, the Moscow government decided to tear down the huge, extremely dilapidated, and antiquated building: it had run its course. In January 2006, the hotel was closed, and in March of the same year, demolition work began. At the time of dismantling, a new hotel-office complex and parking ramp were planned for the soon-to-be-vacant site.

2012

International design contest

In early 2012, President Vladimir Putin announced that by September 2017, the old Rossiya Hotel site would be developed into a modern park. Applicants from more than 27 countries and 420 companies, combined into 90 consortia, competed for a chance to create the landscape-architectural concept. Leading architecture and urban planning experts sat on the jury, including Saskia Sassen, a professor at Columbia University, Deputy Mayor of Barcelona Antoni Vives Tomas, and Martha Thorne, Executive Director of the Pritzker Architecture Prize. The winning proposal came from an international consortium, including architects from New York-based Diller Scofidio + Renfro's and urban planners from Moscow-based Citymakers. Construction of Zaryadye began in 2014.

2017

The making of Zaryadye Park

The park’s landscaping will be completed by September 2017 and the cultural and educational buildings – including a new concert hall under the direction of Valery Gergiev, director of the Marinsky theatre – by spring 2018. Construction of the park’s facilities is being carried out by the general contractor and designer Mosinzhproekt. The project has brought together experts in landscape architecture, urban planning, transport, park management, botany and dendrology, soil science, environmental engineering, and sustainable development, as well as in visual technologies and acoustics. The park’s concept is based on the principle of ‘wild urbanism’ – the organic integration of the park into Moscow’s historical centre and the recreation of landscapes representing Russia’s different micro climates.